In espionage movies, we see international spies with multiple passports, each claiming a different identity. However, we know that each of those passports represents the same person. The trigonometric identities act in a similar manner to multiple passports—there are many ways to represent the same trigonometric expression. Just as a spy will choose an Italian passport when traveling to Italy, we choose the identity that applies to the given scenario when solving a trigonometric equation.

Figure \(\PageIndex\): International passports and travel documents

In this section, we will begin an examination of the fundamental trigonometric identities, including how we can verify them and how we can use them to simplify trigonometric expressions.

Identities enable us to simplify complicated expressions. They are the basic tools of trigonometry used in solving trigonometric equations, just as factoring, finding common denominators, and using special formulas are the basic tools of solving algebraic equations. In fact, we use algebraic techniques constantly to simplify trigonometric expressions. Basic properties and formulas of algebra, such as the difference of squares formula and the perfect squares formula, will simplify the work involved with trigonometric expressions and equations. We already know that all of the trigonometric functions are related because they all are defined in terms of the unit circle. Consequently, any trigonometric identity can be written in many ways.

To verify the trigonometric identities, we usually start with the more complicated side of the equation and essentially rewrite the expression until it has been transformed into the same expression as the other side of the equation. Sometimes we have to factor expressions, expand expressions, find common denominators, or use other algebraic strategies to obtain the desired result. In this first section, we will work with the fundamental identities: the Pythagorean identities, the even-odd identities, the reciprocal identities, and the quotient identities.

We will begin with the Pythagorean identities (Table \(\PageIndex\)), which are equations involving trigonometric functions based on the properties of a right triangle. We have already seen and used the first of these identifies, but now we will also use additional identities.

| \(^2 \theta+^2 \theta=1\) | \(1+^2 \theta=^2 \theta\) | \(1+^2 \theta=^2 \theta\) |

The second and third identities can be obtained by manipulating the first. The identity \(1+^2 \theta=^2 \theta\) is found by rewriting the left side of the equation in terms of sine and cosine.

Similarly, \(1+^2 \theta=^2 \theta\) can be obtained by rewriting the left side of this identity in terms of sine and cosine:

In Section 5.3, we determined which trigonometric functions are odd and which are even. Table \(\PageIndex\) shows these relationships as even-odd identities.

| \(\tan(−\theta)=−\tan \theta\) | \(\sin(−\theta)=−\sin \theta\) | \(\cos(−\theta)=\cos \theta\) |

| \(\cot(−\theta)=−\cot \theta\) | \(\csc(−\theta)=−\csc \theta\) | \(\sec(−\theta)=\sec \theta\) |

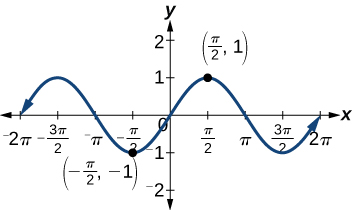

Recall that an odd function is one in which \(f(−x)= −f(x)\) for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f\). The sine function is an odd function because \(\sin(−\theta)=−\sin \theta\). The graph of an odd function is symmetric about the origin. For example, consider corresponding inputs of \(\dfrac<\pi>\) and \(−\dfrac<\pi>\). The output of \(\sin\left (\dfrac<\pi>\right )\) is the opposite of the output of \(\sin \left (−\dfrac<\pi>\right )\). Thus,

This is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex\).

Figure \(\PageIndex\): Graph of \(y=\sin \theta\)

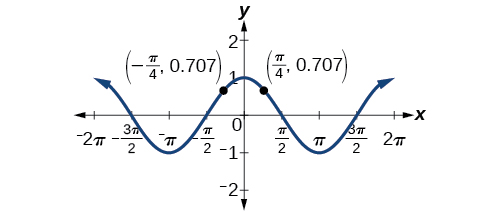

Recall that an even function is one in which

\(f(−x)=f(x)\) for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f\)

The graph of an even function is symmetric across the \(y\)-axis. The cosine function is an even function because \(\cos(−\theta)=\cos \theta\). For example, consider corresponding inputs \(\dfrac<\pi>\) and \(−\dfrac<\pi>\). The output of \(\cos\left (\dfrac<\pi>\right)\) is the same as the output of \(\cos\left (−\dfrac<\pi>\right)\). Thus,

See Figure \(\PageIndex\).

Figure \(\PageIndex\): Graph of \(y=\cos \theta\)

The other even-odd identities follow from the even and odd nature of the sine and cosine functions. For example, consider the tangent identity, \(\tan(−\theta)=−\tan \theta\). We can interpret the tangent of a negative angle as

Tangent is therefore an odd function.

The cotangent identity, \(\cot(−\theta)=−\cot \theta\), also follows from the sine and cosine identities. We can interpret the cotangent of a negative angle as

Cotangent is therefore an odd function.

The cosecant function is the reciprocal of the sine function, which means that the cosecant of a negative angle will be interpreted as

The cosecant function is therefore odd.

Finally, the secant function is the reciprocal of the cosine function, and the secant of a negative angle is interpreted as

The secant function is therefore even.

To sum up, only two of the trigonometric functions, cosine and secant, are even. The other four functions are odd, verifying the even-odd identities.

The next set of fundamental identities is the set of reciprocal identities, which, as their name implies, relate trigonometric functions that are reciprocals of each other (Table \(\PageIndex\)). We first encountered these identities in Section 5.3.

| \(\sin \theta=\dfrac\) | \(\csc \theta=\dfrac\) |

| \(\cos \theta = \dfrac\) | \(\sec \theta=\dfrac\) |

| \(\tan \theta=\dfrac\) | \(\cot \theta=\dfrac\) |

The final set of identities is the set of quotient identities, which define relationships among certain trigonometric functions and can be very helpful in verifying other identities (Table \(\PageIndex\)).

| \(\tan \theta=\dfrac\) | \(\cot \theta=\dfrac\) |

The reciprocal and quotient identities are derived from the definitions of the basic trigonometric functions.

SUMMARIZING TRIGONOMETRIC IDENTITIES

The Pythagorean identities are based on the properties of a right triangle.

The even-odd identities relate the value of a trigonometric function at a given angle to the value of the function at the opposite angle.

\[\tan(−\theta)=−\tan \theta \nonumber\]

\[\cot(−\theta)=−\cot \theta \nonumber\]

\[\sin(−\theta)=−\sin \theta \nonumber\]

\[\csc(−\theta)=−\csc \theta \nonumber\]

\[\cos(−\theta)=\cos \theta \nonumber\]

\[\sec(−\theta)=\sec \theta \nonumber\]

The reciprocal identities define reciprocals of the trigonometric functions.

The quotient identities define the relationship among the trigonometric functions.

Given a trigonometric identity, verify that it is true

Example \(\PageIndex\): Verifying a Trigonometric Identity

Verify \(\tan \theta \cos \theta=\sin \theta\).

Solution

We will start on the left side, as it is the more complicated side:

\[ \begin \tan \theta \cos \theta &=\left(\dfrac\right)\cos \theta \\[5pt] &=\sin \theta. \end\]

Analysis

This identity was fairly simple to verify, as it only required writing \(\tan \theta\) in terms of \(\sin \theta\) and \(\cos \theta\).

\(\PageIndex\)

Verify the identity \(\csc \theta \cos \theta \tan \theta=1\).

Example \(\PageIndex\): Verifying an Equivalency Using the Even-Odd Identities

Verify the following equivalency using the even-odd identities:

Solution

Working on the left side of the equation, we have

\[ \begin (1+\sin x)[1+\sin(−x)]&=(1+\sin x)(1-\sin x), \quad \text \sin(-x)= -\sin x \\[5pt] &=1-\sin^2x \quad \text <(difference of squares)>\\[5pt] &= \cos^2x, \quad \text \sin^2 \theta + \cos^2 \theta = 1. \end\]

Example \(\PageIndex\): Verifying a Trigonometric Identity Involving \(^2 \theta\)

Verify the identity \(\dfrac^2 \theta−1>^2 \theta>=^2 \theta\)

Solution

As the left side is more complicated, let’s begin there.

There is more than one way to verify an identity. Here is another possibility. Again, we can start with the left side.

Analysis

In the first method, we split the fraction, putting both terms in the numerator over a common denominator. In the second method, we used the identity \(^2 \theta=^2 \theta+1\) and continued to simplify. This problem illustrates that there are multiple ways we can verify an identity. Employing some creativity can sometimes simplify a procedure. As long as the substitutions are correct, the answer will be the same.